By Tom Rugman

Foreign Policy Analyst

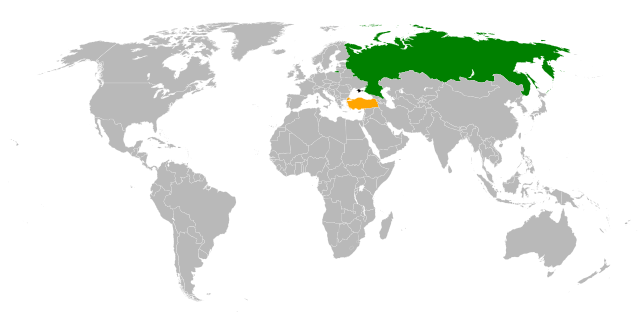

Marriages of convenience are all too common in global politics. But the war in Ukraine may yet deal a fatal blow to one of the most curious examples - that between Turkey’s Recep Erdoğan and Russia’s Vladimir Putin. When considering the global phenomenon of authoritarian strongmen, it is sometimes tempting to suppose that such leaders fall neatly on a common axis, sharing a similar style and conviction. But Erdoğan’s manoeuvring around the war in Ukraine suggests that he may be calling time on what he once called a “special relationship”.

Last week, the Turkish president finally acquiesced to Swedish membership of NATO, a move that will test Russia-Turkey relations and that came after months of frustration and obstruction. Erdoğan had previously insisted on several guarantees in exchange for Swedish approval, with admission to the alliance requiring the agreement of all members. Two of his key demands had been the extradition of Kurdish exiles in Sweden, and opening the door to further talks on Turkish EU membership. It is unclear which guarantees Erdoğan has been able to exact, but the optics are that Ankara is angling for pragmatic engagement with Europe, much to Moscow’s chagrin.

More than this, Turkey has been providing support to Ukraine through indication of NATO membership approval and the supply of military equipment.This includes a varied arsenal of precision-guided missiles, drones, and armoured vehicles. The tension in Russo-Turkish relations provoked by the war in Ukraine was also demonstrated by Erdoğan’s hosting of Volodymyr Zelenskyy last week. On Zelenskyy’s return to Ukraine, he was accompanied by five Azov Battalion commanders who had been in Turkey since last year, and whom Russia understood would remain there. The battalion is a designated terrorist organisation in Russia; Putin’s press secretary, Dmitry Peskov, called the move “a direct violation of the terms of existing agreements”. Indeed, Moscow was so slighted by this apparent double-dealing that last Monday the chair of the Federation Council Committee on Defence and Security suggested Turkey might be added to its list of “unfriendly” countries.

The balancing act that Erdoğan has attempted in Ukraine has largely been based on economic measures, with the centrepiece being the Black Sea Grain Deal, which Turkey mediated. The deal was drawn up in order to alleviate rising global food prices following the invasion, allowing Ukraine to continue to export via the Black Sea. But a deterioration in relations between Russia and Turkey appears to have compromised the deal, which expired on Monday with no sign of renewal. With Russia-Ukraine relations severed, the deal was structured via two ‘mirror’ agreements between Turkey and both parties to the conflict in Ukraine. But Putin expressed his displeasure, asserting that the deal had met none of his demands; this contrasted with Erdoğan’s statement that he and Putin agreed that the deal should be extended. Elsewhere, Turkey had previously set itself aside from the EU in not prosecuting Russia as vigorously in the form of sanctions, subscribing only to those imposed by the UN, as well as continuing to import Russian oil. But in March, Erdoğan halted the transit of some European goods through Turkey to Russia without an official explanation, and absent any sanctions regime of its own.

Back in 2016, Russia and Turkey announced a normalisation of ties following a tense period of relations stretching back to the 1990s. The move was a surprising development in the light of an incident the previous year in which Turkish (American-supplied) F-16s shot down a Russian aircraft close to the Turkish-Syrian border. Subsequent economic and travel sanctions imposed by Moscow would later be reversed, but the timing and context of this normalisation made it apparent from the start that this was to be an interest-based relationship, and one that interests could not feed for long.

The farce of warmer ties is perhaps best illustrated by the number of proxies in which Turkey and Russia compete for influence. In Syria, Russia has been one of the Assad regime’s main backers, whilst Turkey has aligned itself with the Syrian opposition in the hope of cultivating a favourable position for itself in a post-Assad Syria. Turkey also has an interest in containing and pacifying the Kurds in Syria, represented by the Syrian Democratic Forces and in its primary component, the People’s Defense Units. Not by coincidence, Russia has not repudiated Kurdish aspirations, with reports that the PKK maintains an office in Moscow.

In Libya, both Turkey and Russia have committed forces to opposing factions in the civil war, with Turkey backing the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA) and Russia supporting al-Thani’s Tobruk-based government. Such engagements illustrate that this relationship is an uncomfortable one to say the least, with Tripoli - presumably under advice from its allies - coordinating drone strikes against Wagner mercenaries remaining in the country just last month.

Turkish involvement in the Caucasus meanwhile represents a more direct intrusion into Russia’s backyard. Turkey’s long-hostile relationship with Armenia has consequently compelled it to send Azerbaijan support in the form of military drones and F-16s. Sinan Ulgen, of the Center for Economics and Foreign Policy Studies, suggests that the purpose of Turkish involvement here is not to eliminate Russian influence but to leverage Moscow on other fronts such as Syria and Libya. Meanwhile, Russia’s support for Armenia, which despite CSTO security commitments remains lukewarm, is likely to be escalated if Turkey continues to embed itself in the region.

The current status of these conflicts, in which the tide generally seems to be with Russia and its allies, might suggest that on the back of his election victory, Erdoğan may now be favouring a policy of confronting Moscow more directly. Turkey’s domestic political environment may be an important consideration here, with opposition leader Kılıçdaroğlu - who came away with a substantial 47.82% - accusing Russia of interfering in the election. Even despite gaining an endorsement from Putin in the run-up to the election, Erdoğan may now wish to distance himself from Moscow even if Turkish public opinion is not behind a declaration of hostility towards Russia.

So, has Erdoğan overplayed his hand with Putin? It is clear that far from being a committed member of an ‘axis of evil’, the Turkish president is intent on charting foreign policy independent of Western and Russian strategies if at all possible. And having recently won re-election in a country where democratic backsliding has cemented itself in the last decade, we can expect Turkish strategic priorities to remain consistent in this regard. A Turkey engaging in more active or aggressive competition with Russia is not the same as a Western-aligned Turkey, and the latter prospect is probably not one that will be meaningfully fulfilled any time soon. Despite Erdoğan aiming to develop talks on Turkish EU membership, this is an impossibility as long as Turkey continues to occupy Northern Cyprus, at a minimum.

Such considerations might suggest that Erdoğan’s snubbing of Putin regarding NATO expansion is a shot in the foot. But this is only the case if we discount this third possibility: that we should understand and expect Turkey to be an increasingly influential regional power of its own accord. For Russia’s part, it is unclear what stock Putin places in his personal relationship with Erdoğan, given that he seems to be willing to give up the Black Sea deal, for instance. Commentators may have overstated the extent of Turkey’s leverage or Putin’s dependence when discussing the war in Ukraine, but no doubt Putin will be eyeing Ankara warily, as its moves will be a major consideration in Russian strategies in its neighbourhood.

Great revisions of hostile relations can occur; one can look to the relationship between France and Germany, Germany and Israel, or any number of other examples. But the assertion that ‘friendly’ Russo-Turkish relations cannot last does not need to rely on historical enmity or a litany of past abuses and disputes; it is merely a

consequence of geopolitical realities. This is the case not only because of the space Russia and Turkey share - the Black Sea and spheres of influence in the Middle East - but also because of other ties the two countries maintain elsewhere. For example, Erdoğan’s PR exercise of positioning himself as a protector of Muslims globally stands in contrast both with Putin’s record in Chechnya, and warming ties between Russia and nations such as Israel and India. Elsewhere, Turkey has expressed an interest in expanding its influence in Central Asia with fellow Turkic nations - potentially intruding in Russia’s backyard. And Russia for its own part is increasingly propping up Iran, a key regional rival of Turkey’s. The US’s own record of multipolar diplomacy shows that such contradictory sets of alliances are possible, but often create unanticipated problems and may ultimately be unsustainable. The latest era of Russia-Turkey relations was predicated on at least the tacit assumption that one party would have to stab the other in the back first. If that is what Erdogan is now doing, he has chosen his moment carefully. Now, Turkey awaits Russia’s next move.

Comments