By Daniel Piper

Senior Analyst

Concerns over the dominance of the Chinese state in world economic affairs is an issue voiced by many global leaders over the past several years. Indeed, the Dutch Intelligence Agency’s Annual Report, published in April 2023, cited China as the ‘greatest threat to Dutch economic security’ that the nation currently faces, superseding an increasingly antagonistic Russia and internal EU challenges.

However, this divide is scarcely more visible than it is when examining the progression of BRICS. Beginning as a Goldman Sachs marketing tool in 2001, the BRICS economic alliance has been formalised for over a decade. It currently controls around 25% of the world GDP and 42% of the global population and has the potential to come an increasingly important player in world economic and political affairs over the next few years, in particular. However, data appears to indicate that China will lead that charge, and the remainder of BRICS may have to increasingly kowtow to Beijing in order to continue their economically beneficial relationship.

A recent paper by economist Dan Ciuriak argues that BRICS has always been unequal in terms of economic parity, with China in a period of acceleration under the reforms of Deng Xiaoping and Jiang Zemin, whilst Russia reckoned with the fall of the Soviet Union, Brazil tried to stabilise their currency, and South Africa enjoyed a post-Apartheid economic boom. This makes China’s subsequent economic success even more impressive, becoming the world’s largest economy by world GDP share in Purchasing Power Parity in 2016, according to the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook database.

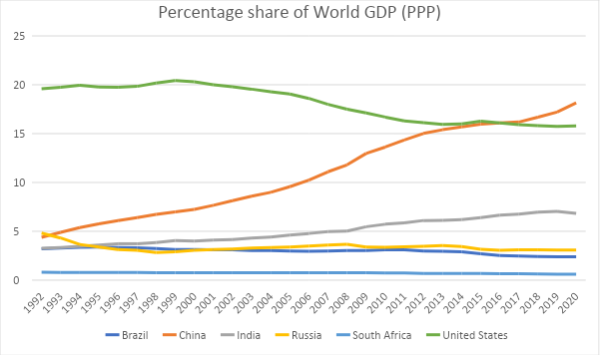

If we use this metric to examine the rest of BRICS, China’s dominance is clearly apparent. In the graph below, China is demonstrably the only economy of the BRICS five to have made meaningful economic progress in the period 1992-2020 (pre-pandemic). Neither Russia nor Brazil nor South Africa has ever accounted for more than 5% of world GDP, and both have seen their percentage share decline. India’s share rose by 3.5 points, but this pales in comparison to China’s 13.8% growth.

This graph and economic metric are but one example of the growth of China into a geopolitical superpower, coupled with an active military ranked by the Global Firepower Power Index as the third most powerful for 2023, and within 0.01 points of the top-ranked United States and second-ranked Russia, the latter being engaged in an active military conflict with Ukraine, hence the strengthening of their armed forces.

Further still, China is the only nation of BRICS with the economic power to adjust the group’s

trajectory. A BRICS currency, floated by Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, will die as a concept unless China decides to abandon the power of the Renminbi, the currency currently rivalling the US dollar for its position as the World Reserve Currency. This will happen, logically, because China will refuse to give up such a strategically significant position, along with the power to manipulate their currency’s value. This is particularly important to China, as it allows them to keep their exports competitive in the global marketplace through currency devaluation – something not easily possible with a single currency like the Euro.

China also dwarfs the impact of the New Development Bank, set up by BRICS nations to promote economic development in smaller nations, and existing as an alternative to the Euromerican dominated World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Whilst this new bank has ‘extended $32.8bn in loans’, China is believed to have bilaterally lent the equivalent of almost $1 trillion dollars, according to the Financial Times. China, as such, is acting as the de facto lending power to small nations over and above the specific financial instrument which it helped to set up to facilitate loans. Evidently, China is the economic backbone of BRICS, cementing its position in the bloc as, if nothing else, the first amongst supposed equals.

Most of the loans bilaterally provided by China form part of its ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative, commonly known as the Belt and Road Initiative. Whilst this topic warrants an article of its own, there are some standout examples which typify the Chinese push to grow its economic influence. Sri Lanka, for example, borrowed money from China to build a deep-water harbour to engage better in Global Trade, only to lease the port to China for 99 years when they were unable to repay their loans, as documented by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a nonprofit policy research organisation in the United States.

More notable is that the Belt and Road Initiative has very little interaction with India, China’s subcontinental rival, fellow BRICS member, and now the most populous nation on Earth. Through strategic planning and the careful cultivation of both economic dependents and allies, according to a 2017 paper by Jacob, ‘the BRI may be understood as a long-term strategic initiative’ designed to ‘convert China’s current economic might into diplomatic influence’, enhancing the power of China in world trade and diminishing a potential future world superpower.

China, particularly in recent years, has also been exerting its influence intra-bloc, attempting to force through policy changes and sometimes creating explicit hostility. It should not be forgotten that China has a ‘longstanding military rivalry’ with India over territorial disputes in the Ladakh region and Arunachal Pradesh, along with exploiting the ‘no-limits’ partnership between Premier Xi and Russian President Putin. According to Reuters, China is currently buying Russian oil rather than non-sanctioned oil because they are able to purchase it for a price below the world market price, which Beattie argues is a trade-off for ‘diplomatic cover’ for Putin over his attack on Ukraine.

Whilst it could be argued that China’s oil trace with Russia is a result of the strengthening of ties between the BRICS nations, it is not overly cynical to suggest that China is attempting to take advantage of a potentially lucrative opportunity, exploiting Russia’s need for money to continue funding its violent Ukrainian campaign.

Moving to a purely political standpoint, China stands in direct opposition to a majority of the bloc in its position as ‘an economic, technological, and strategic rival’ to the United States. Whilst Russia assumes a similarly anti-Western stance, Brazil, India, and South Africa continually seek closer ties with Europe and the US. Brazil, for example, finalised a trade deal in 2019 between the EU and South America’s MERCOSUR bloc, and India remains an integral part of the US’ Asia-Pacific Bloc, Quad. Notably, however, this places China and Russia into the same sub-bloc – BRICS’ most economically, militarily, and diplomatically powerful members, one of which is beholden to the other for oil payments and support.

Outside of the Global East/West divide, China is able to distance itself from internal bloc divisions on policy, content to continue industrialising and developing with Russia and the rest of the world. For example, Russia stands to benefit from Climate Change, as Rare Metals and oil are released from the melting Siberian permafrost and its ports become more usable – Vladivostok and Arkhangelsk are currently unusable for over one hundred days a year due to the freezing of water and machinery. Comparatively, Brazil under the da Silva administration has taken a far harder line on climate change, with ‘the most ambitious’ green transition plan for the country set to be announced in August or September of 2023. Brazil is not set to benefit from climate change, with forest fires in the Amazon rainforest increasing in frequency annually, and 2019’s fires projected by ecologists to cost Brazil upwards of USD$3 trillion, according to Gill.

Why, in that case, is China not dominating the bloc and directing each of the nations’ domestic and foreign policy? From an international perspective, it is simply because the member nations want to avoid Chinese domination from becoming ingrained. South Africa announced on July 20th that more than forty nations were interested in joining BRICS, with twenty-two formally requesting admission to the bloc. An examination of this list, however, reveals that many such nations, including Kazakhstan, Gabon, and Iran, are directly involved in the Belt and Road Initiative, and are therefore, if not beholden to China, likely to favour China in intra-bloc disputes. This is justified by the importance of the Belt and Road initiative to central governments seeking to expand their country’s influence in global affairs and speed up their economic development. Further, more developed nations like Cuba, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates have also applied to join, bringing with their support considerable economic power and, in the case of the latter two states, large amounts of oil.

One must also consider the challenges facing the Chinese state, and those which it will face over the coming years and decades. Official data published in January 2023 indicated that China’s population decreased year-on-year by 850,000 people, the first fall since the famine of 1961 under Mao’s Great Leap Forward. Al Jazeera further notes that searches on the Chinese search engine Baidu for pushchairs have fallen by 41% and searches for baby bottles are down more than 33% in the same period, indicating a fall in the number of individuals looking to have children.

Perhaps the most famous indicator of China’s demographic troubles is seen in the demographic diagrams, which indicate that a large number of working-age people, those same people who have driven economic development in China since the 1980s, are approaching retirement. Whilst birth rates did increase in the 1980s, in a period known as the ‘Deng Boom’, these individuals are now not having enough children to support a large increase in welfare spending which will come as a result of more people relying on the state pension.

Considering this factor may sway one to believe that BRICS will return, in the coming decades, to an organisation on a more equal footing. However, with India’s birth rate still rising and the nation still industrialising, the title of ‘Great Power’ may be usurped by India, leaving them in the dominant position within BRICS that China currently holds.

In the 22 years since O’Neill et al. of Goldman Sachs published a paper formally grouping the BRIC nations, the world has been hit by various economic events, yet China has consistently outperformed expectations of growth. Even as its growth slows, it holds an unequivocally dominant position within the organisation, and has shown a willingness and ability to procure soft power. As Ciuriak asserts, BRICS cannot be cohesive and an economic organisation whilst only the largest member is on track to become an advanced economy. To regain influence, the remaining BRICS countries must continue industrialising. To regain parity, the remaining BRICS countries have much further to go.

Comments