Captagon Cowboys: Syria’s Rise as a Narco-State

- James Robert Loughton

- Aug 23, 2023

- 10 min read

Updated: Nov 28, 2023

Editor in Chief

This article was originally published May 31, 2023, in the York Politics Review:

https://yorkpoliticsreview.uk/2023/05/31/captagon-cowboys-syrias-rise-as-a-narco-state/

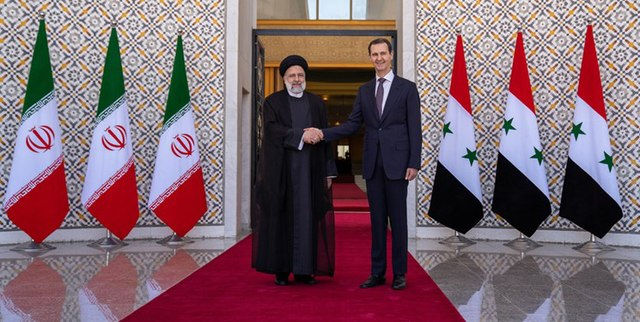

Assad Still Standing

More than a decade of civil war has left Syria in ruins; despite the Syrian Government retaking swathes of formerly rebel and ISIL-controlled territories, any resemblance of a structured state is long gone. The devastating earthquakes that hit Northern Syria and Turkey on 6th February have worsened the nationwide permanent humanitarian crisis. Western sanctions originally in response to a brutal government crackdown on protests inspired by the Arab Spring remain in place and have crippled the Syrian economy. Smaller-scale conflict, natural disasters, water scarcity, fuel shortages, mass starvation, and few viable industries for employment have prevented the Syrian economy from rebuilding itself. Yet there is one market in Syria that has boomed, influencing Syria’s re-entry into Arab League and escape from international isolation. The Captagon trade...

Captagon is a synthetic drug that has transformed Syria into a narco-state. First developed in the 1960s, fenethylline hydrochloride (more commonly known as ‘Captagon’) is a synthetic amphetamine that stimulates the central nervous system, increasing the user’s physical and mental capabilities. Highly addictive and cheap to produce, Captagon now dominates drug scenes across the Middle East. Pills have been flowing out of Syria at an inconceivable rate; 47 million pills were discovered in a single warehouse shipment in Riyadh last year. Eighty-four million pills were seized in a shipment to Salerno in 2020.

80% of the world’s supply is produced in Syria and regions of Lebanon under the control of pro-Syrian government militant groups. At the head of this vast network of illegal drug production is thought to be Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. With most avenues for domestic production of goods gone, Captagon is now Syria’s biggest export providing Assad with a lucrative means to fund his regime and influence the geopolitics of the Middle East.

The Arab League, a diplomatic organisation tasked with coordinating states in the Arab world, voted on 7th May to reinstate Syria’s membership. Syria had been excluded from the organisation twelve years prior to the eruption of civil conflict. Leading members, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, initially punished the Syrian regime whilst assisting rebel groups. However, they have since reversed this isolation with rapid normalisation talks taking place since the start of the year. These states have publicly justified developing relations by conceding that Assad has emerged victorious over opposition groups, with government forces providing a stabilising force for Syria.

Behind closed doors, however, the Captagon trade poses one of the greatest motivators for diplomatic action. Syria’s ability to flood the region with drugs has pressured its enemies into concessions, but how did we get here?

Chaos Creates Opportunity

In 2018, Greek authorities intercepted a cargo vessel leaving the Syrian port of Latakia. Bound for Libya, the vessel contained three million Captagon pills worth around 100 million USD. At first, the ship was assumed to be part of an ISIL drug-running operation; ISIL groups have been known to traffick drugs from Libya to Sicily. Furthermore, Captagon first came to attention as the drug of choice for ISIL fighters.

Referred to as the “drug of the Jihad”, Captagon pills have been found in ISIL militant hideouts for years. The seized cargo vessel, however, belonged to traffickers affiliated with the Syrian Government, highlighting close ties between Assad and the Syrian underworld. Latakia Port has developed into a hub for black markets; Captagon, among other drugs and Iranian weapons, serves an important role in increasing Assad’s financial capabilities.

A report published on 28th March 2023 from the British Government states that Syria’s Captagon trade could be worth up to $57 billion, placing it at three times the combined trade of Mexican cartels. This figure is dauntingly massive and has been criticised by several Middle-Eastern research groups for exaggerating the true market value. But, even conservative estimates place it at above $10 billion. The report also listed notable figures believed to be in control of the Captagon trade, including militia leaders, politicians, and members of the Assad family. Syria, therefore, serves as the optimal logistical environment for organised drug production.

ISIL’s rapid expansion left large-scale areas devoid of law and order, promoting people left unemployed to manufacture pills for an expanding market. When forces loyal to the Syrian Government retook these areas, they had little interest in shutting down operations. Instead, Government fighters took advantage, facilitating transportation networks and protecting manufacturers. In return, they receive a hefty chunk of the profit.

In 2022, leading Syrian analysts placed the value of seized shipments of Captagon at around 6 billion USD, with only 5 to 10% of shipments seized by authorities; this total market value dwarfs the Syrian Government’s claimed official exports valued at 800 million USD. Profits have stabilised and strengthened the structure of Assad’s regime, funding militias that fight on his behalf. When civil war erupted, the armed forces were left in disarray; in their place came the Shabiha mercenaries belonging to Assad’s Alawite ethnic minority community.

Assad’s minority background and commitment to secularism drew support from minority groups who feared a Sunni Arab-dominated government. Alongside the Shabiha were the Popular Committees, militant groups from Christian, Druze and Shia backgrounds. Shia fighters from outside Syria flocked to fight, and an estimated 10,000 Iraqis and Lebanese, Afghani and Pakistani fighters were deployed under Hezbollah’s command. These groups were armed, funded and merged into the National Defence Forces, a paramilitary network of volunteers. All these belligerent groups required regular government funding, so the Captagon trade became the life support of its ability to wage war.

Captagon’s deadly addiction has brought all warring parties of the conflict together. Production is common in areas still under Islamist control, Kurdish control and especially in the rebel-controlled North. What separates the rebel’s attempts from the Government’s drug trade is scale. The Syrian Government now operates as a cartel. Smugglers flocked to government regions for stability, forging connections with pro-Assad warlords and businessmen. Syrian armed forces, primarily the notorious Fourth Division of the Syrian Arab Army, act as the muscle. Iranian-backed Iraqi PMF forces have provided greater opportunity to smuggle by land whilst Hezbollah provided ports in North Lebanon, opening up the sea lanes to Europe.

The power vacuum created by the civil war formed an opportunity for the Government to lessen its economic dependence on Iran and Russia. A report by the Newlines Institute claimed that “elements of the Syrian government are key drivers of the Captagon trade, with ministerial-level complicity in production and smuggling”. Drug trafficking is no longer a crime accepted by the Government and is engaged by militias indirectly linked to the Government. Instead, it has become an integrated means of economic survival for Assad’s regime.

Brothers in Crime

At the heart of this collaboration between criminal gangs and government forces is Maher al-Assad, commander of the Syrian army’s elite Fourth Armed Division and brother of President Assad. Like North Korea’s Kim dynasty, the Assad family has been central to Syrian politics for 50 years. Following the 1963 March Revolution, revolutionary commanders from Syria’s Alawite minority community seized power. Among these commanders was Hafez al-Assad, who, in

1966, launched a second coup against his former allies, securing his total domination over Syria.

Hafez would then elevate his family to top roles in the government/military, and following his death in 2000, his son Bashar would succeed as President. Despite being older and more experienced, Maher would retain a less prominent role in Syrian politics. Whilst his brother became the face of Syria, Maher became the brain of Syria’s underworld. After taking command of the 10,000-strong Republican Guard, Maher expanded his military career by seizing the elite Fourth Armored Division, previously under the control of his uncle Rifaat al-Assad.

Following the Civil War, Maher acted as a powerful warlord, facilitating illegal businesses in regions under his control. Military forces under his command directed manufacturing and smuggling, transporting shipments of pills from laboratories to the port of Latakia. According to Salah Malkawi, a Jordanian analyst, Maher’s soldiers have provided military training to smugglers. Regions under the control of the Fourth Division are rife with military checkpoints, making it impossible for smugglers to operate without the support of the blessing of Maher.

An AFP investigation found that Captagon labs get “the raw material directly from the Fourth Division, sometimes in military bags”, with these military-run factories producing Captagon that is supplied throughout the region, including rebel groups opposed to the regime.

Maher directly profits from narcotrafficking, his primary source of income for funding government forces under his control. However, he is not the only member of the Assad family to be involved. The EU imposed sanctions against two cousins of Bashar and Maher this year, accusing Wasim Badi al-Assad and Samer Kamal al-Assad of running a “regime-led business model” that operates Captagon factories, with the revenue contributing towards government funding.

Connections also exist in Lebanon, where the Captagon trade has been dominated by Hassan Muhammad Daquo, nicknamed the “King of Captagon”. Daquo has long been rumoured to engage in close business deals with members of the Assad family, acquiring grand places in western Syria previously occupied by Assad family members. Connected to both cousins and operating under the protection of Maher’s military forces, his drug empire ambitions seemingly ended following his arrest and imprisonment in 2021. However, the Lebanese druglord’s operations have continued to operate thanks to strong connections with Hezbollah militant group.

Lebanese Connection

In neighbouring Lebanon, narcotrafficking equally flourishes, thanks mainly to the trade’s backing and support by Hezbollah. Originating from Lebanon’s fifteen-year civil war during the 70s and 80s, Hezbollah formed as a Shiite resistance organisation to remove Israel’s influence over Lebanon. The “Party of Allah” has been designated a terrorist organisation by several international organisations, including the Arab League and European Union.

Despite this, Hezbollah operates freely as a mainstream political movement in Lebanon, controlling large areas autonomous from Lebanese authorities, receiving the label of a “state within a state”. Hezbollah has maintained strong connections to Iran, the group’s main backer on the international stage, but its strongest regional partner has long been the Syrian Government. Since the start of the Syrian Civil War, Hezbollah has collaborated closely with the Government, sending its fighters to battle rebel forces on the Syrian-Lebanon border. This collaboration is also present within the Captagon trade. Hezbollah has been accused of turning Lebanon into a “narco-state”, working with the Fourth Armored Division to transport pills through its territory and permitting Captagon factories to operate under its protection.

The King of Captagon, Daqou, has been photographed with Hezbollah militants, maintaining a close connection to Hezbollah leaders, securing his comfortable stay in a Lebanese prison within Hezbollah territory. This relationship exemplifies the wide-scale integration between Hezbollah and drug gangs; tens of millions of pills have been seized from vessels leaving Hezbollah-controlled ports in Northern Lebanon. In 2021, Saudi Arabia placed a temporary import ban on all Lebanese products due to widespread drug smuggling.

The Lebanese military is primarily focused on cross-border threats and terrorist violence; Lebanese authorities also find it increasingly difficult to operate in Hezbollah territories. This has resulted in Lebanon serving as an extension of the Syrian Captagon trade. Hezbollah leadership have officially denied involvement. However, Lebanese investigators have reported farmers in Hezbollah territories being encouraged to switch to Captagon production, an appealing opportunity for struggling farmers hit especially hard by Lebanon’s economic crisis. With the Lebanese state going bankrupt and Hezbollah’s power continuously growing, the appeal to produce Captagon for the Shiite militants may be hard to resist.

Drug Diplomacy

The combined Captagon exports from Syria and Lebanon are drowning the streets of many Gulf states. Saudi Arabia has been hit particularly hard by it, becoming the world’s largest Captagon market; in 2021, the kingdom’s customs body seized 119 million pills, these pills serving as the drug of choice for Saudi youth. Saudi authorities have begun cracking down with increased seizures of land and sea shipments. The situation has been compared to the significant cocaine seizures made by US authorities in the 1980s, providing good headlines but having a limited impact

. For young Saudi workers, Captagon allows them to continue working for days without the need for sleep, one young taxi driver describing it as enabling him to “double my earnings and is helping me pay off my debts”. The highly addictive pills are destroying communities across the Gulf states; Jordanian hospitals, for example, are struggling to keep up with the number of patients suffering from over dosage and life-threatening side effects.

“Hallucinations, nausea, vomiting, seizures, high blood pressure and heart palpitations” are all common experiences, according to an addiction services group based in Saudi Arabia.

For Saudi Arabia and other Middle-Eastern nations struggling to tackle this epidemic, restoring ties with Syria may be the only way to shrink the Captogan market effectively. It is no coincidence that nations hit the hardest have become increasingly open to restoring dialogue with the Syrian Government. Assad has been accused of leveraging the drug trade against enemy nations; CNN reports that the regime is “signalling to states considering normalisation that they could reduce Captagon trafficking as a goodwill gesture”. Arab League talks between regime, Jordanian and Iraqi diplomats have included solutions to tackling drug trafficking, highlighting a strategic need for normalisation ties to combat the Captagon trade.

There is merit to this strategy; since Jordan began normalisation with the Syrian Government in 2021, there has been a nine per cent decrease in drug abuse cases from Captagon, and seizures have increased to a total of 69 million pills being seized in 2022. Furthermore, on 8th May, only a day after Syria’s re-entry into the Arab League, a suspected trafficker, Marai al-Ramthan, operating on the Syrian-Jordanian border, was killed in a Jordanian airstrike.

The “poor man’s cocaine” is reaching new markets every year, shipments are being seized from Oman to Italy, Gulf states are unable to tackle a drug fueling its working populace efficiently, and the Syrian Government is earning billions from it all. The civil war is entering its final stages as rebel groups desperately cling to their final war-torn territories; it is clear to all that Assad is going nowhere. As nations opposed to the Assad regime slowly reincorporate the pariah state back into the international system and the Arab world, perhaps diplomacy is the only viable solution to reducing the Captagon trade.

Update

Since this article’s first publication, a number of events have occurred relating to the seemingly unstoppable flow of Captagon throughout the Middle East. For the first time publicly, President Assad has openly acknowledged the crisis, denying Syrian government involvement and instead placing blame on Western-backed rebels. In a recent interview Assad stated:

"When there is war and the state is weakened... The countries that contributed to creating chaos in Syria bear the responsibility for this, not the Syrian state”.

This public denial and shifting of responsibility has been followed by statements from Iranian authorities decrying Captagon's abuse and its deadly effects on Iranian society. Yet despite this, Iran still refuses to ratify the Financial Action Task Force, an international non-governmental organisation aimed at combating illicit markets. This refusal is logical, Iran does not wish to make its own illicit activities vulnerable by opening up to international NGOs, however, Iranian and Syrian officials publicly denouncing the trade signals potential for change.

Assad’s readmittance into the Arab League alongside Iranian rapprochement with Turkey and Saudi Arabia is reducing tensions. Reforged economic connections - primarily through Gulf state sponsored UN-building projects - will finally provide Assad with legitimate means of rebuilding, no longer having to rely on black markets and sanction dodging. Because of this, both actors seem now to be quietly shutting down their involvement whilst publicly blaming the crisis on foreign actors to muddy the water. However, with continuing large-scale busts occurring across the Middle East - 6 millions pills captured in one bust alone by Omani and Saudi officials in June - and increasing interest from the US, UK, and EU in limiting the trade potentially flaring up new tensions, this epidemic is far from ending.

Commentaires